1. The Square, looking north towards the church

The Archbishops of Canterbury had a house at Wrotham until the 14th century and must have owned the advowson of St George’s church, which is a very large and fine building (part of the Archbishops’ house survives embedded in a later building just south-east of the church). The body of the church looks 14th century from outside, though with a good Perpendicular tower, typical of Kent, dominating the little market square and a porch of the same date.

2. Exterior of the church from the south-east

The windows of the south aisle and the south side of the chancel are early 14th century – if the heavy Victorian restoration renewed them accurately. The east window, which looks late medieval, is a curiosity: it was originally the west window of Wren’s St Alban, Wood Street in the City and was brought to Wrotham in1958 when the body of the blitzed St Alban was demolished. It is gothic revival (or survival) of the 17th century.

3. Interior of the church looking east

The spacious nave has arcades of the 13th century, the north slightly earlier than the south. The chancel arch is also of the 13th century. Above it there is a passage in the thickness of the wall, accessed from the rood stair in the south aisle, with small windows opening towards the nave and chancel. The purpose of this arrangement, which seems to be unique, is unknown.

4. Pulpit

The extraordinary stone pulpit, which must be the most elaborate Victorian pulpit in Kent, was designed in 1861 by architects Newman & Billing and carved by J W Seale. The carving of the angel group supporting the body of the pulpit is of the highest quality.

5. Rood screen

Not many rood screens survive in Kent. This one is Perpendicular and has square-headed lights. It is rather heavily restored.

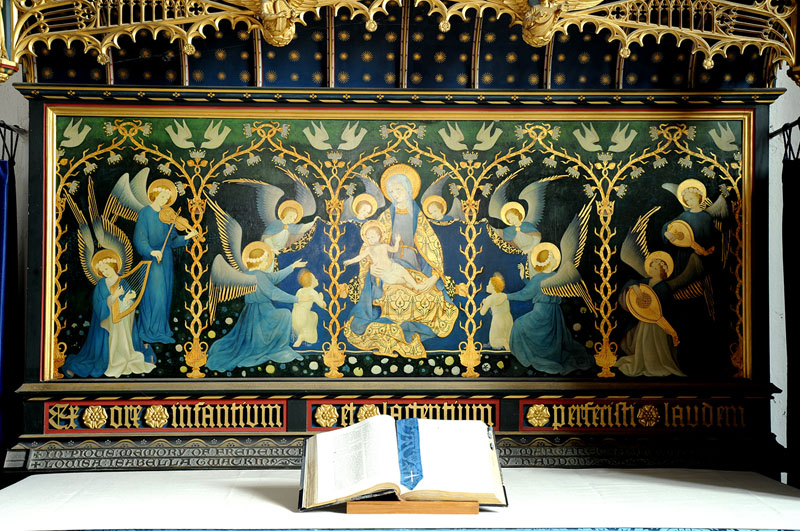

6. Altar retable in south aisle

The ‘English’ altar at the east end of the south aisle has an exquisite retable, or reredos, designed by Ninian Comper in 1907. It is painted in the style of the Wilton diptych, commissioned by Richard II and now in the National Gallery. There are other, equally good Comper fittings at nearby Kemsing.

7. Detail of east window of south aisle

There are few better parish churches in Kent at which to enjoy Victorian stained glass. A number of the major firms producing glass are represented. The east window of the south aisle was designed in 1861 by J M Allen and made by Lavers and Barraud. It depicts the Virgin and saints – in this case St Agnes. With its acid colours, this is an outstanding, early example of the wonderful flowering of stained glass design in England in the 1860s.

8. Detail of the brass to James Pekham

The church has an array of brasses dating from the late 15th to the 17th century set in the nave floor before the rood screen. The photograph shows five of the daughters of James Pekham, who died in 1532. As with most late medieval English brasses, the quality of the engraving is not high.

9. Detail of the monument to Nicholas Miller

Wrotham has a large number of post-Reformation monuments. This one, in the south aisle, commemorates Nicholas Miller, who died in 1661, and may have been carved by the London statuary Thomas Stanton. It is made of black and white marble, a fashionable combination which first appeared in England in the 1620s.

10. Monument to Lucretia Betenson

The monument to Lucretia Betenson in the north aisle is the best in the church. She died in 1758. The monument, with its portrait bust in high relief and rococo details is in the style of Louis Francois Roubiliac, the greatest sculptor to work in England in the 18th century and must have been designed by him, but the carving lacks Roubiliac’s finesse and may have been done by his pupil Nicholas Read. The epitaph is worth reading. The only signed work by Roubiliac in Kent is the monument to Richard Children at Tonbridge.