The weather was not kind to us on the afternoon of Tuesday 13 September but a large group of Friends – over 50 people – visited three good churches in west Kent, ending with a splendid welcome from the vicar of Marden, the Reverend Nicky Harvey and members of her congregation, who gave us a fine tea. It was very pleasing to see that the number of people participating had recovered to pre-Covid levels.

St Luke, Matfield had never been visited previously by the Friends in their 70-year history of church tours. The parish came into existence only in the 1870s, having formerly been part of Brenchley and its first priest, the Reverend Charles Storr (son of the then vicar of Brenchley), commissioned his cousin, the young architect Basil Champneys, to design the new church. Both men were grandchildren of the celebrated Regency goldsmith Paul Storr and were related to several prominent Victorian churchmen. Champneys designed a remarkable little building, unique in Kent, which presciently foreshadows the Arts and Crafts movement that began 10 years later. Although built in 1874-76, it looks like a church of the 1890s.

St Luke, Matfield – exterior seen from the west

Champneys produced a refined and intensely pretty church of almost domestic scale. It appears much more like a Surrey or Sussex church than a Kentish one, with its bellcote at the west end and half-timbered porch. The quality of the exterior masonry of Wealden sandstone is very fine and the architect must have taken the greatest care over every detail, especially the rather wilful Decorated window tracery.

St Luke, Matfield – exterior seen from the north

The interior is just as good and benefits from having all its original fittings and furnishings, designed by Champneys. The font, sedilia and nave benches are especially attractive.

St Luke, Matfield – font

St Luke, Matfield – bench end

The east window is by Charles Eamer Kempe and there are two others by the same firm, though both made after Kempe’s death. The glass looks exactly right in this building.

St Luke, Matfield – detail of the east window, the Adoration of the Magi

Champneys became an early member of the Artworkers’ Guild, founded in 1884, which was a leading influence on the Arts and Crafts movement. St Luke’s is not an Arts and Crafts church – if there is such a thing – but it prefigures that movement with its beautifully cut stonework and fine furnishings. Champneys went on to do much work at Oxford and Cambridge, including his greatest achievement, Newnham College at the latter university.

All Saints, Brenchley is a stately, predominantly 14th century building, in a fine village with many good timber-framed houses, including the medieval former vicarage which stands next to the lychgate.

The church has an aisled nave, chancel and transepts, though there is no evidence that it ever had a central tower. The western tower, which is 14th century below and Perpendicular above, is slightly ungainly because of the excessively massive buttresses and two uppermost stages which are too short.

All Saints, Brenchley – the tower

The spacious nave has 13th century arcades, though the nave aisles, transepts and chancel are (or were – the chancel was rebuilt in1814) all of the 14th century. Both chancel and chancel arch are of great width.

All Saints, Brenchley – interior looking east

The nave has a splendid crown-post roof which must be 14th century, to judge by the pierced tracery above the arched braces which support the tie beams. It has a richly painted celure in the eastern bay, above where the rood would have stood. This must be one of the most handsome crown-post roofs in any Kent church.

All Saints, Brenchley – the nave roof

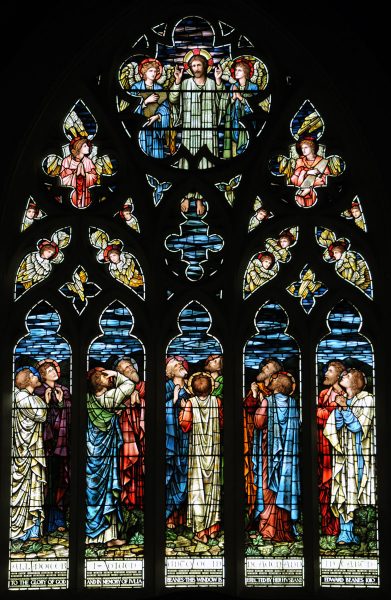

The fittings are unexceptional. The roodscreen has gone, though its dado survives reused as the fronts of the choir stalls and the stair to the rood loft remains within a sort of stone cage in the south transept (very similar to Wrotham). The glass of the east window depicting the Ascension is a late production of Morris & Company, made long after Morris himself had died. Like the windows by the same firm at St Stephen’s Tonbridge, it is probably by J H Dearle.

All Saints, Brenchley – east window, the Ascension

There is a good array of wall monuments, the best those to Walter Roberts +1652, with half figures of Roberts and his wife which charmingly touch hands; and that to Stephen Hooker +1775, a chaste neo-classical piece by the eminent sculptor Joseph Wilton. Few churchyards in Kent contain a better display of headstones and chest tombs than Brenchley, though few of us stopped to look at them in the rain.

All Saints, Brenchley – monument to Walter Roberts & his wife

The most arresting feature of St Michael and All Angels, Marden Is undoubtedly the glass of its east window and any description must start there. Designed and made in 1963 by Patrick Reytiens, who had made his name a few years earlier when collaborating with John Piper on the great baptistery window at Coventry Cathedral, it depicts Christ in Majesty from the Book of Revelation. It is a powerful design in strong colours, the lead cames used to produce jagged shapes. It must have seemed especially startling when new because so much glass of the immediate post-war years – as demonstrated in other windows at Marden – was so sentimental and, frankly, rather feeble. The smaller windows in the north and south walls of the sanctuary are also by Reytiens.

St Michael, Marden – east window, Christ in Majesty

The church itself seems a little tame after these fireworks. Apart from the 13th century tower with its pretty weather-boarded top and the Perpendicular north chapel, the building is mostly of the 14th century.

St Michael, Marden – exterior from the north-east

St Michael, Marden – interior looking east

The best evidence are two fine Decorated windows in the north aisle but much of the other window tracery seems to date from restorations in the 1860s and 1880s. John Newman suggests that the latter was by Sir Thomas Jackson, who was usually less heavy-handed than this.

The best of the fittings are the south door within the porch and the font cover. Doors are often overlooked but this one is hard to miss, is stylishly fluted and must be of the 16th century. The font cover is dated 1662 and is of the type with doors, as at East Malling and Newington-next-Sittingbourne. There are other examples in East Sussex. Marden’s cover is very handsome.

St Michael, Marden – font cover