On Thursday, 9th June a group of 40 members of the Friends visited three churches in east Kent – St James, Staple, St Mary, Woodnesborough and St Nicholas, Ash, where we had a good tea. There were talks on the history of each building. The weather was fine, all the churches made us most welcome and the three buildings made a most interesting trio.

Members awaiting a talk on Woodnesborough church

St James, Staple is essentially an early 14th century church, though it has an earlier tower and some tantalising Norman and even Saxon evidence at the west end of the nave.

St James, Staple: exterior

The tower, to judge from its lancet bell-openings, is of the 13th century, embellished with buttresses and a west doorway and window in the Perpendicular style. But there are pieces of Romanesque scallop capital embedded in the west wall on either side of the tower arch and John Newman, in the relevant Buildings of England volume, records an upper window in the tower east wall which has been claimed to be Saxon. The window is said to be visible internally, though we could not see it: perhaps that means that it is visible within the tower but not from the nave. We did observe, however, what looked like a rough, blocked opening in the tower east wall, outside and just above the ridge of the nave roof. The body of the church consists of an unusually long nave and chancel, with a short north aisle and a north chapel.

St James, Staple: interior looking east

All of this, to judge from the window tracery (largely restored by Street), is of the early 14th century. The fine east window has five, cinquefoil-headed lights, rather like the contemporary east window at St Mary, Selling. There is no chancel arch and the good crown-post roof covers both the nave and chancel. The arcade to the nave north aisle is a Perpendicular insertion.

St James, Staple: interior looking west

Of the fittings, much the best is the font which is octagonal and Perpendicular. It has symbols of the Evangelists on the bowl and wild men and lions round the stem – a common East Anglian type but unique in Kent. That it was ordered in Norfolk or Suffolk for this very church is suggested by the symbol of a pilgrim on the bowl representing St James.

St James, Staple: font

The only stained glass of note is a pretty window in the nave of 2007 by Mary Tucker. There is an excellent series of 17th and 18th century wall monuments in the north chapel, culminating in a refined monument with portrait medallion to Sir William Lynch, date of death 1785. It is unsigned: one would like to know who the sculptor was.

St James, Staple: monument to Sir William Lynch

Finally, the lychgate is worth a look, both because it has two entrances, one wider than the other, and because it is dated 1664. The thing which immediately strikes one about St Mary, Woodnesborough is that the top of the tower, which has a wooden cupola surrounded by a balustrade, 18th century additions to a structure built about 1200. Once painted white, they are a charming survival not found elsewhere in the county.

St Mary, Woodnesborough: tower

The nave was built just before 1200, to judge from the arcades. The north arcade has piers which are alternately round and octagonal, with deeply scalloped capitals: this, as John Newman has pointed out, is related to contemporary work in the choir at Canterbury Cathedral.

St Mary Woodnesborough: interior looking east

The south arcade has crude square piers which may be a little earlier. The chancel has lancets and must be of the 13th century, save for the Decorated east window. The church suffered a heavy restoration at the hands of Ewan Christian in 1884: all the window tracery and the west doorway are completely renewed, which makes the survival of the tower cupola and balustrade all the more surprising. The sedilia, 14th century and with miniature vaulting, is much the most interesting of the fittings, though there are also Georgian altar rails and Royal Arms.

St Mary, Woodnesborough: vault within sedilia

There is good glass by Burlison & Grylls in the chancel and three more recent windows by FW Cole.

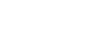

St Mary, Woodnesbough: glass by FW Cole

There is a minor wall monument in the chancel to Thomas Blechenden, dated 1661, which may be by Thomas Stanton.

St Mary Woodnesborough: monument to Thomas Blechenden

St Nicholas, Ash is much the largest and finest of the three churches visited that afternoon. It is a big, cruciform church, well-placed above the village street. Its tall central tower with spirelet is visible from afar.

St Nicholas, Ash: exterior

The building dates, apart from the tower and north chapel, from the 13th century. The most telling feature is the nave north arcade, with round piers (which are oddly different from each other) and arches with immense chamfers like those in the arcades at Woodchurch, which must be roughly contemporary. The details of the north chapel are decorated. The tower is Perpendicular, inserted into the earlier building on fine crossing piers.

St Nicholas, Ash: interior looking east

The south transept was rebuilt in the 17th century and the whole building restored by William Butterfield, who added a porch and replaced the east and west windows with new tracery of his own, insensitive design. There are a font and a chandelier of the 18th century, two sets of Royal Arms – Charles II and George III – the former discovered hidden behind the latter in recent years, and a good pulpit by Butterfield.

St Nicholas, Ash: Arms of Charles II

There is also much glass by Ward & Hughes, later Curtis, Ward & Hughes; indeed, there is nowhere better in Kent to observe the development of their glass in the period 1860-1900. There is fine glass of 2007 by John Corley in a north aisle window.

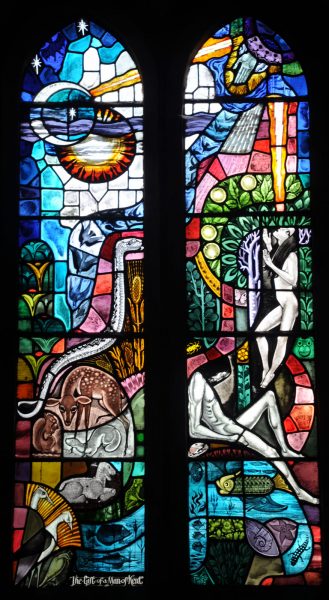

St Nicholas, Ash: glass by John Corley

But what matters most at Ash is the monuments, especially the medieval ones, of which Ash has the best collection of any parish church in Kent. There are four with effigies. The best are those to Sir John Leverick, a finely carved 14th century knight; and to John de Septvans, who died in 1458, and his wife, their effigies of alabaster.

St Nicholas, Ash: monument to Sir John Leverick

He wears a livery collar of Esses, denoting his Lancastrian allegiance, elaborate armour and, very unusually, is shown with markedly receding hair. There are also fine wall monuments and brasses of the 17th century.

St Nicholas, Ash: monument to John de Septvans

St Nicholas, Ash: monument to John de Septvans